Shaping network society: a quick note on my new job

Most of you know that starting May 1st I moved to CSC, one of the big global IT systems integration and outsourcing players. It has been an amazing first three months and I am looking forward to writing down some of my experiences. It is thrilling and exciting to see the interplay between network technologies, processes, and governance unfold as we try to shape our emerging network societies.

Expect more soon…

Power-Shift or Media-Shift? The Twitter Revolutions in Iran, Tunisia, and Egypt

Are we observing a tectonic change in the Arab world, parallel only to the revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe 1990? Are Facebook and Twitter the equivalent of the levee en masse in post-revolutionary France? Or is Egypt’s just-in-time Internet blocking working?

The Egyptian, Tunesian, and Iranian protesters were not the first to utilize social media to organize and amplify their voices. During the French riots in 2005, in the Zimbabwean opposition uprising in 2008, in the Greek protests in late 2008 and during the youth riots in Budapest 2006, social media played important roles. In the Ukrainian 2004 Orange Revolution, flashmobs, organized online, contributed to the revolution’s success. During the Greek riots, Twitter was used massively. And a first reading of the case seems to suggest that the spread of sympathy worldwide among the Internet community triggered protests in many European cities. The impact on the international level has caused scholars to speak about the rise of a new global phenomenon: the “networked protest,” a phenomenon for which the Internet is valued as being crucial for its occurrence. Social networking technologies are involved in many of today’s social movements and seem to transform traditional modes of protest politics. Many-to-many media enable a new form of collective action never observed before.

One-to-Many and Many-to-Many

What makes the decisive difference between traditional mass-media and networked social media is the logic at work. Traditional Western mass media is exclusively broadcast media, i.e., one-to-many media, where direct feedback is impossible. In many-to-many media, the emitter and the recipient coincide. This theoretically allows the empowerment of new social actors. But it is more complicated, as media production in a networked realm is malleable: It can include “information broadcasting,” i.e., sent from one-to-many (e.g., blogging, micro-blogging such as Twitter), it can be a “conversation” between many (a forum or social networking), or it can be a “project” that is collaboratively produced by many only to thereafter be broadcast (Wikipedia, Indymedia, Ushahidi). The difference between “conversations” and “projects” is that socially produced conversations are not purposeful in the sense of generating a common output, while collaborative production concentrates on the output of the collaboration. The latter two are naturally exclusive to many-to-many media, as social actors within the network produce media for other social actors within the network, while broadcasting can take place on many-to-many or one-to-many platforms (television, radio, print).

Does it Change the Powerscape?

What is missing in existing studies of the revolutionary potential of many-to-many is a persuasive framework to describe the interplay between traditional media, social media and power relations in society. In an article under review at Oxford Internet Policy Journal, Sophie van Hüllen and I argue that there are two possible heuristics: The power-shift and the media-shift hypothesis.

The Power-Shift Hypothesis

The power-shift hypothesis assumes that many-to-many media will empower actors successfully utilizing social media. The notion of power itself is, in reference to Max Weber’s definition, understood as the ability of a social actor to enforce her will, even against the will of other actors. To better understand the interaction of many-to-many media and traditional power relations, we differentiate between two relevant power patterns: Coercive power (Weber) and structural power (cf. Foucault’s or Castells’s notion of power through “discourse”). Coercive power is caused by a superiority based on physical or synthetic advantages of one actor over the other. Power can be exercised by either fear or physical violence. Structural power is the fixation of power relations through institutions and culture in which social actors are dominated by others. The construction of institutions and cultures is channeled through communication. The power to influence the meaning and value defining process is labeled as agenda setting power. The ability to control social media, i.e., the construction of meaning, should then lead to changes in agenda-setting and institutional power arrangements as we are possibly seeing in Tunesia and Egypt (not in Iran).

The Media-Shift Hypothesis

The media-shift hypothesis assumes that the Internet and more specifically the mainstreaming of many-to-many media, such as blogging, collaborative editing, and social networking, has changed how we produce and consume information on all levels. However, it is not that many-to-many media is superseding mass media, but rather entering a complex interplay with mass media, where it is substantially impacting the media cycle, but not automatically altering social power relations. The hypothesis assumes that many-to-many media are closely embedded into the traditional channels of mass media. Thus the media-shift hypothesis reminds us that the use of a different media does not automatically entail a power-shift. Web 2.0 technologies introduce a new “mediascape,” but no new “powerscape.”

In Conclusion

Both the power-shift and the media-shift hypotheses are relevant heuristics to understand the impact of social networking technologies on revolutionary politics today. Social media are relevant for agenda setting, organization, coordination, motivation, and the provision of real-time information. Traditional Western mass media, today are dependent on online social media platforms to report about the protests. However, mass-media journalism is not displaced by the network public sphere. Journalistic processing adds value for the audience. Similar configurations likely will be observed in the next years. That is why the development of theories of the public sphere should be promoted in the sense of that coexistence of both mass media and social media with their respective modes of production. Clearly, we are confronted with a complex rearrangement of existing power structures and in need of frameworks that allow us to think these through intelligently. Until we have a fully-developed theory of our networked societies, heuristics such as the power-shift or the media-shift hypothesis can be helpful to describe, explain, and predict collective action. Even if the empirical evidence suggests that today many-to-many media have transformed the mediascape, but not the powerscape, we are shooting at moving targets. We need to carefully develop heuristics that allow us to understand and explain the complex interplay of social media and power politics.

Read the article by clicking here…

Rethinking Copyright for Social Production

In the early 21st Century, social production is starting to play a major role in how we live our lives and create wealth – just like the feudal system was superseded by capitalism, social production is increasing its footprint in our economies and societies.

Social production on a grand scale has become possible because of digitization and network technologies that allow us to collaborate across space and time. However, its success is not technologically determined. Social production needs production processes with interfaces to potential contributors that allow granular and modular contributions, checks and balances that ensure quality control. And process managers that are able to engage outside contributors without relying on the classical ‘modern’ modes of aligning interests, such as contracts, monetary incentives, or force. And a legal framework that fosters it.

Historically, social production has always existed as a mode of collective action, the 17th Century idea of the invisible college is only one example. However, only in the 21st Century have we developed the transaction cost reducing network technologies and the open source mindset that is making social production the default mode of creating value. No new business model is possible in 2010, if it does not at least include a social aspect.Therefore, any strategist today needs to ask, “how do structure the value web or transform my existing value chain so that I leverage the potential of openness?”

Copyright and Social Production

The value added of most products today takes place in the digital realm, therefore result of our processes normally are digital products, covered under existing copyright law. However, our intellectual property rights regimes and organizational cultures have not yet been adapted to facilitate social production and its results. The GPL and other open licensing models are “hacks” to our existing ‘one-person, one-product’ intellectual property rights framework, not a fundamental rethinking that is necessary when confronted with such a fundamental challenge as the incorporation of social production into our network economies and societies.

Therefore, we need to address the following questions:

- How do base metaphors shape the grammar of our normative thinking on creativity and value creation?

- What alternative base metaphors could be imagined as foundational for a value creation framework?

- When talking social production, what is the original position, from which we analyze questions of value creation and distribution of benefits?

- How do we translate these political theory questions into legal principles?

- How do we operationalize legal principles into a functioning system?

- How can we evaluate economic and societal effects of such a counter-factual system?

Rethinking/Rebooting US-Mexican Relations

In early December at the Harvard Kennedy School, I co-chaired a workshop where we asked, “should we aim to re-shape the policy discourse on North American integration, by applying some of the lessons learned from how the European Union interacts with poor and fragile states at its South-Eastern borders?”

This idea is at once simple and obvious (learn from global best practices) and radical (it forces us to rethink almost everything we assume about national sovereignty and the contemporary US and Mexican policy discourses), therefore, it needs careful reflection.

The backstory

Let me start with a caveat – we came to this question from very different perspectives. Mary and I are not integration scholars. Mary is working on development issues in Latin America and she heads the Mexico program at the Kennedy School. I have headed a public policy program in Mexico for some years, but today am interested in how network technologies shape public policy and head the center for public management and governance at the business school in Salzburg. I have left Mexico three years ago and only go back once or twice a year.

We have worked together for the last 7 years in our roles as coordinators of an academic exchange agreement between Tec de Monterrey and the Kennedy School, on several research projects, and executive programs. During all this time, North American integration has been the backdrop to our discussions. However, 10 years after NAFTA, it was not the topic we dared to touch in our work.

In parallel in Europe, there have been three major, even revolutionary, changes in European border regimes in the past two decades. These represent transformation in both thinking and practice with regard to borders and international cooperation to secure them.

- removing the EU’s internal borders (Schengen)

- extending the Schengen acquis and institution building to countries with initially weak institutions in Central and South East Europe (Schengen enlargement)

- defining reforms of security institutions, border regimes and policing in countries on the Eastern border of the EU in return for visa-free travel (visa road maps)

They have all been very much security oriented—precisely because they have involved revolutionary changes. The Germans, for example, have accepted that “their” external borders are protected first by each other, then by Poles, and soon by Romanians – this goes way beyond giving up the Deutsche Mark for the Euro.

In effect, the German external border has moved to the Hungarian-Romanian border and is going to move to the Romanian-Moldovan border in the Spring of 2011. Therefore, making sure that security risks are minimized has been crucial to the acceptance of each successive step. From the perspective of countries like Poland and Romania, the approach was just as radical. The European Union specified and controlled processes that are integral to the sovereignty of any nation. However, the combination of medium term carrots (visa-free travel, accession), with clearly specified sticks (process-reengineering, quality control) worked wonders for these countries.

So from time to time over a Margarita in Mexico or a Samual Adams in Cambridge, we would discuss the argument that there must be something to be learned from the European process. This summer, finally, while we were co-teaching in a summer program here in Cambridge that Mary was organizing, we met Gerald Knaus, from the European Stability Institute, one of the master-minds behind the European success story (or at least a facilitator).

The Analogy

Analogies are structural mappings from one familiar domain onto a different domain. They are not true in themselves, but potentially helpful to shed light on difficult problems.

The analogy is that the challenges and opportunities Mexico and the US are facing structurally comparable to the challenges and opportunities that Southern and Eastern European countries and the European Union are facing.

The assumption is that at least some of the practices that have shown tremendous success in Europe can be transferred to the Mexican-US situation.

Our Vision – Join us in the upcoming year and help with research, awareness-creation, and fund-raising!

- Develop a research community that is concerned about the topic.

- Develop a set of best practices from the European analogy that can be implemented in the North American context.

- Shape the policy discourse on North American integration for years to come.

- And address the biggest policy challenge that the United States is confronted with at this time in history.

Learning from the European Analogy?

On Thursday, we (Mary Hilderbrand, Gerald Knaus, and me) are bringing together a group of academics and policy makers from the European Union, Mexico, and the US for a first workshop at the Harvard Kennedy School. We will be exploring the idea that the challenges and opportunities Mexico and the US are facing structurally comparable to the challenges and opportunities that Southern and Eastern European countries and the European Union are facing, so that at least some of the practices that have shown tremendous success in Europe can be transferred to the Mexican-US situation. We call this “learning from the European analogy.”

US-Mexican relations have become gridlocked on many fronts. Immigration from Mexico to the US is a difficult political and policy issue that has been resistant to solution. Trafficking in drugs and weapons is not seriously addressed at a regional level. Both the US and Mexican policy elites have taken a defensive posture in the discourse rather than thinking in terms of integration, even as economic integration is moving forward.

By taking a step back and using a comparative approach, we want to develop a new approach towards North American integration. We assume that there are interesting lessons to be learned from the European integration process. Looking back at the last twenty years, we can observe a surprising success in the formerly divided European continent.

- Several countries with lower GDPs than Mexico in 1990 have achieved integration into the European Union.

- Open borders have been extended to include countries marked in the recent past by high levels of corruption, crime, and violence. Balkan states formerly at war now have murder rates comparable to that of Sweden.

- With access to production capacities and human resources in the East, the European Union has become one of the world’s most competitive economic spheres.

Although there are remaining problems and issues to be confronted, transformation has been swift and the results are generally positive. The changes have been accomplished by offering attractive incentives—specifically, visa-facilitation, clear roadmaps, and membership—as well as through defining a clear European body of law (the EU acquis), using it strategically, offering advice, and ensuring compliance through clearly specified mechanisms.

Perhaps most significantly for potential relevance to North America, the EU has been able to export its ideas of security to a much poorer half of the European continent, allowing it to handle threats facing EU citizens better. The integration of South East Europe has been approached through the framework of visa road maps, starting with the exchange of visa facilitation schemes and progressing to visa-free travel in return for meeting demanding road-map conditions. Whereas the prospect of EU accession is not available in any other context, the visa road-map framework holds promise to inspire debates in other contexts, including the relations between the US and its southern neighbors, especially Mexico.

Security, Visa Road Maps, and Borders in the EU

There have been three major, even revolutionary, changes in European border regimes in the past two decades. These represent transformation in both thinking and practice with regard to borders and international cooperation to secure them.

- removing the EU’s internal borders (Schengen)

- extending the Schengen acquis and institution building to countries with initially weak institutions in Central and South East Europe (Schengen enlargement)

- defining reforms of security institutions, border regimes and policing in countries on the Eastern border of the EU in return for visa-free travel (visa road maps)

They have all been very much security oriented—precisely because they have involved revolutionary changes. The Dutch and Germans, for example, have accepted that “their” external borders are protected first by each other, then by Poles, and soon by Romanians. In effect, the Dutch external border has moved to the Hungarian-Romanian border and is going to move to the Romanian-Moldovan border in spring 2011. Therefore, making sure that security risks are minimized has been crucial to the acceptance of each successive step.

This has been an effort shaped by interior ministries, to such an extent that it has often been criticized as “fortress Europe”. Yet that has been central to its credibility and success. There have been no leaps of faith, no romantic notions that borders do not matter. EU citizens care intensely about issues of illegal migration, transnational organized crime and insecurity. These changes have, therefore, involved defining and enforcing very clear targets.

The changes have not occurred overnight. Based on institution building and the creation of new networks of cooperation and trust, this has been a generational project that began in the mid 1980s and is ongoing. It has been incremental and experimental in implementation. And the project of a continent- wide reform of border management and security cooperation is still expanding: there are now serious debates on visa road-maps for Ukraine, Moldova, Turkey, Kosovo, and even the South Caucasus. In the last year the visa issue has also moved to the center of the Russia-EU dialogue.

Relevance for US and Mexico

US-Mexican relations have not developed along the same lines nor at the same pace as the integration of Central and Eastern European countries into the European Union. Trade barriers were lowered or removed through NAFTA, but strong opposition continues in both countries; some parts of the agreement have not been fully implemented; and deeper economic integration has been limited. The labor markets of the two countries are highly interdependent, and illegal immigration into the US is a major and increasingly difficult political and economic challenge, but progress on immigration policy reform has been stymied. Whereas the economies of Central and Eastern European countries have developed rapidly, Mexico’s economic growth has been slow. Tensions between the original European Union countries and their neighbors have been reduced; tensions between Mexico and the US over migration and security issues are growing.

We believe that exploring the analogy of the successful European experience, and in particular the visa road map framework, can make a contribution to developing new ways of thinking about the North American relationships. The immediate objections, beyond the barriers of domestic politics, will surely be that Mexico is too poor, too corrupt, and too racked by violence and insecurity to think of integrative responses rather than defensive ones. The brief review above suggests, however, that the situation in North America and the barriers to be overcome are perhaps less different from the recent EU experience than is generally recognized.

Therefore, serious comparative analysis that looks at the political, economic, institutional contexts; the regional relationships; the nature of the challenges; and policy and political options is needed, to explore whether there are elements of the EU experience that might be adopted and adapted within the North American context. A new integration project along such lines would need serious political capital, but without research that builds the basis for new approaches, there is little hope for change. Therefore, our challenge is twofold:

On the research side, we need…

- to learn more about the similarities and dissimilarities of the respective integration processes. Does the analogy hold? What are its limitations?

- To codify the successful algorithms of integration in Europe and translate them into the North American context.

while on the policy dimension, we need…

- to develop a sensitivity for the analogy in the discourse.

- to lobby for policy interventions that are designed along the lines of the European approach.

That is a fairly big research and policy program, where we need to think in decades, not years. Join us!!! Next workshops are coming up.

Teaching Learning [to] Organizations in Turbulent Times

I just spent two wonderful days with the Dutch interior ministry at their Trends in Troubleshooting conference. The very original core question posed to us be the conference organizers around Jorrit de Jong from HKS was, how do we think strategically about the feedback we get from citizens and what can we learn from them? I had been asked to lead a workshop on organizational learning and had the honor to be reflector on the final panel of the day, a round-table, where we tried to wrap our mind around the question, how to translate learning into corporate/governmental strategy.

I am the father of three little kids, and they never stop to amaze me. They learn really fast and enjoy it. Johanna who will turn two months on Saturday has just learned to smile, when I smile at her, Max, who is in a Latin American kindergarten, now corrects my Spanish at the dinner table, and Helena who just started first grade and is surprising me with new perspectives on how she sees herself. The trajectory from Johanna to Helena is breathtaking, and there is more to come. Most people I know, love to learn. Most organizations seem to hate it. Why?

A learning organization is an institution that facilitates the learning of its members, continuously reflects and transforms itself, and thereby creates an institution that becomes greater than its parts. According to Peter Senge, a learning organization has five main features; systems thinking, personal mastery, mental models, shared vision and team learning.

Systems thinking is the process of understanding how things influence one another within a whole, personal mastery refers to individuals willing to continuously improve, mental models are the assumptions that shape the thinking in organizations that are to be reflected, learned and unlearned, shared vision is the defined common goal, and team learning, the knowledge management structures, allowing creation, acquisition, dissemination, and implementation of this knowledge in the organization.

So we are confronted with a puzzle, that even though as humans we love learning, as organizations we seem to shun it.

Maybe the metaphorical mapping of learning (a psychological concept) onto organizations (a political/managerial concept) is problematic. However, even though the anthropomorphization of organizations that comes with the mapping is problematic – organizations are not humans, just as fast cars are not girl friends – from empirical experience, we know that organizations that achieve the ability to learn, to act as if they were human, over-perform. We could loosely map Johanna, Maximilian, and Helena on the stages that we expect a learning organization to go through:

First order learning: execute the leaders’ ideas. Command and control.

The original story on organizational learning can be found in the introduction to Sun Tzu’s text the art of war. Sun Tzu Wu was called to Ho Lu the king of the Ch’i state and asked if he could teach his strategic approach to the king’s concubines. After confirming this, he started to teach them to follow his marching orders.

After they do not follow his commands for the second time – stating if a command is clear and the troops do not follow, it must be the fault of the officers – he beheads the acting officers (the king’s favorite concubines). Thereafter, the troups follow his commands perfectly. Almost like Johanna now responds to my smiles. Not like Helena, who became a different person after she started school. Even today, after more than 2000 years since Sun Tzu, most organizations still resemble Johanna and and not Helena. They are good at adapting to the changes suggested by their generals.

Second order learning: collect data, develop hypotheses and test them. Feedback loops, hypothesis-driven, data-driven.

In 1994, Police Commissioner William Bratton of the New York Police Department created CompStat, a leadership and management strategy designed to reduce the city’s crime rate. It was based on accurate and timely intelligence, effective tactics, and relentless follow up on tasks.

“Collect, analyze, and map crime data and other essential police performance measures on a regular basis, and hold police managers accountable for their performance as measured by these data.”

First, they collect and analyze data to determine the type and level of results that the organization is producing, to detect its important “performance deficits,” and to suggest policies and practices that might produce improvements, an organizational learning strategy. In the words of performance leadership guru Bob Behn:

A jurisdiction or agency is employing a PerformanceStat performance strategy if it holds an ongoing series of regular, frequent, periodic, integrated meetings during which the chief executive and/or the principal members of the chief executive’s leadership team plus the individual director (and the top managers) of different sub-units use data to analyze the unit’s past performance, to follow-up on previous decisions and commitments to improve performance, to establish its next performance objectives, and to examine the effectiveness of its overall performance strategies.

Third order learning: reflect the role of the organization in its greater eco-system and adapt to it.

Third order learning is reflexive learning that adapts the structure of the organization to new needs in real time. In a world conceptualized as stable third order learning did not play a central role. Once processes were in place to deal with an issue they just needed to be executed well, something that Irwin Turbett from Warwick referred to as managing tame problems or in Michael Porter’s language, positioning. However, problems also come in other forms: crisis and wicked problems. Crisis are situations, were decisions need to be taken in real-time und imperfect information, so he suggests control as the way to deal with them. I am not fully convinced that he is correct in his analysis, because today we have decentralized crisis management tools such as Ushahidi or Twitter. Wicked problems on the other hand are issues that are not amenable to algorithmic solutions and they can change through time. Addressing them through a Porter positioning strategies or by aiming to optimize existing processes is actually dangerous. As we are moving into a world where transformation is becoming the default, flux as Heraclite would call it, we need to develop organizations that can deal with changing environments, i.e. wicked problems.

Learning Organizations in Turbulent Times

Today, the ability to adapt to a turbulent world is probably the single most important capability of successful organizations, think Netflix, which had to reinvent its revolutionary business model less than five years after it had developed it. Adaptive organizations embrace experimentation and constant reflection in order to keep pace with incessant change. They utilized managed evolution—in which activities and strategies continuously evolve in response to change, but most importantly, they build curiosity into the process. And that is what we as humans enjoy – maybe all organizations should strive to be like first-graders that cherish the challenge of transformative thinking.

Open Statecraft: Strategic Thinking for a Many-to-Many Society

We live in a world where information and communication technologies have confronted us with new logics of collective action that allow new forms of organization that need new forms of strategic thinking. With the digitization of value creation and the ability to collaborate on value creation across space and time, we have been able to move from a one-to-many, or mass society, to a many-to-many, or network society. A reduction in the transaction costs of collaboration to the level that is possible with or many-to-many media, allows new forms of organizations that collaborate openly in value chains across space and time. Such open value chains need new forms of organizational strategy and leadership if they shall live up to their promise. There is much writing on the new logic of many-to-many society and there are some very practical how-to-guides, however, what is missing is a fundamental reflection on what strategy will look like in a many-to-many world.

what would machiavelli do?

In philosophical terms, we are missing a realist perspective on the fundamental transformation we are experiencing. In keynotes and seminars, I have expressed this need with the question, „what would Machiavelli suggest in the 21st Century?“

Machiavelli was the earliest thinker that was able to see the new modern paradigm and translate it into strategic advice. He understood the perpetual governance crisis of modernity that developed when authority was not anymore legitimated by a transcendent source, i.e. God. Where until the 16th Century an allusion to god or nature was sufficient to explain human governance, he unearthed the relevance of immanent legitimation and formulated it as strategy advice to the prince. We are living through a similar time, the shift is just as profound. We are moving away from the idea of hierarchical organizations in business, government and civil society into a world of networked and project-centered open value chains. However, our conceptual vocabulary and our culture is still stuck in the 20th Century and, therefore, we do not yet fully realize their potential. What is missing is a strategy guide to this brave new world. Machiavelli took up the challenge of trying to make sense of a world that was moving from understanding itself as deterministically following the transcendent will to a world of freedom and choice. In an analogous fashion, we have to try to understand the underlying principles of many-to-many society to outline strategies for successful collective action.

There are two major drivers of many-to-many society: the ease to connect (technology) and the willingness to connect (culture). The ease to connect stems from technologies that allow us to ignore territorial space and linear time. We can post an answer to a question in a forum that was asked several years ago on a different continent. The person that has asked the question might have moved on, but the answer might be relevant to someone in the future that is not even born today. However, without a willingness to interact, without a network culture, the ability does not lead to a changed world. It is not technological determinism, but the interplay between new social practices and enabling technologies that have transformative potential.

living in a low transaction cost society

With the radical reduction of the transaction costs of collective action through many-to-many technologies new form of organization becomes possible. Commons-based peer production is a term coined by Harvard Law School professor Yochai Benkler to describe a new model of economic production in which the creative energy of large numbers of people is coordinated (usually with the aid of the internet) into large, meaningful projects, mostly without traditional hierarchical organization or financial compensation. He distinguishes commons-based peer production from (a) firm production where a centralized decision process decides what has to be done and by whom and (b) market-based production where tagging different prices to different jobs serves as an attractor to anyone interested in doing the job. If this mode of collective action is viable, we need to ask how to structure such interactions and how to lead such processes.

Over the last 30 years, we have been observing a move from black box production, with a focus on optimizing the value chain, to co-production and its focus on supply chain management, to open production on user-generated work-flow-platforms such as Wikipedia and Ubuntu, but also facebook and twitter. This means that strategy changes from competitive strategy (positioning) to communicative meta-strategies (persuading and community creation).

openness as strategy

Open value creation consists of open policy making and the management of the open value chain. The distinction is slightly arbitrary but useful. It allows us to differentiate between coming up with a value generating process (policy) and repeatedly creating the value (value chain). Open value creation is possible because of new technologies that allow us to structure idea generation and information aggregation in digital form. The core technologies of open value creation are the wiki, a principle-based, user-generated platforms, with flexible moderation capacity, the forum, a question driven user-generated knowledge platform, blogging, a core message with feedback/discourse loop, and work flow management and visualization tools such as enterprise resource planning, process mapping tools, think SAP, Oracle, SugarCRM, etc. Together they allow us to structure policy and value creation processes, by enhancing ideation, deliberation, i.e. commenting and discussion, collaboration, generating values, and accountability, i.e. through the parsing of data to control processes. Therefore, the architecture of our value creation processes is of utmost concern. How do we design such processes? The simple answer is Larry Lessig’s “code is law” (1998), which says governance can be encoded into software, as in the first rule of twittering: “thou shalt not write more than 140 characters” where enforcement is automatic, technically, you cannot send a tweet of more than 140 characters. So in our simplest many-to-many society, code, law, strategy, and enforcement are one.

However, in order to fully utilize open value creation strategic transparency is necessary. Strategic transparency is a management approach in which most decision making is carried out publicly and the work flow has open application interfaces. It is a radical departure from existing processes, where (a) decision making was closed, to ensure security and the discretion of the decision makers and (b) the work flow was a black box, where outside intervention would be looked upon as outside meddling. In decision making strategic transparency ensures access to draft documents, allow commenting, and include the public in final decisions. For the work flow, you need to design application interfaces that allow the public to access the work flow in real time, participate in a granular and modular fashion. In a many-to-many society we need to rethink most of our conceptual frames.

Therefore, counter-intuitively, if he were alive today, Machiavelli, the hard-nosed realist, would advice the princess to create open value chains with interfaces to outside stakeholders both in policy and implementation, from research and development to after-sales.

Rethinking Idle Time

This weekend, I was playing around with my new Amazon Kindle 3. I was loading as many classics (Plato, Aristotle, Sun-Tzu and Cory Doctorow) that are freely available onto the Kindle, on the hunch that whenever I would have some idle time, I would use it to reflect on the great thinkers of all ages. It reminded me that for several years, I had wanted to write on the topic…

Idle time is a concept that was introduced into the English language quite early, as an action that is void of any real worth, usefulness, or significance; leading to no solid result; hence, ineffective, worthless, of no value, vain, frivolous, trifling. [Oxford English Dictionary] First mentioned in 825: Dryhten wat eohtas monna foron idle sind (whatever that actually means in modern day English). Idleness always carried a negative connotation. Only in the 21st Century, has idle time turned into the biggest asset humanity has at its disposal to create value.

The metaphorical mapping of the term from the human to machinery arrives in the 19th Century, as in to run idle, to run loose, without doing work or transmitting power. first found in a patent application by Mr Milton in 1805 (Patent No. 2890) “As near..to each active wheel as a workman may think proper, low, strong idle wheels..are to be placed..ready in case of an active wheel coming off, or breaking, or an axle-tree failing, to catch the falling vehicle.”

In the 20th Century, it expanded its use to computers, where it is defined as the time during which a piece of hardware in good operating condition is unused. With networked computers, the idea was that idle time of distributed processors could be put to good use, as long as it can be managed – SETI@home is only one example.

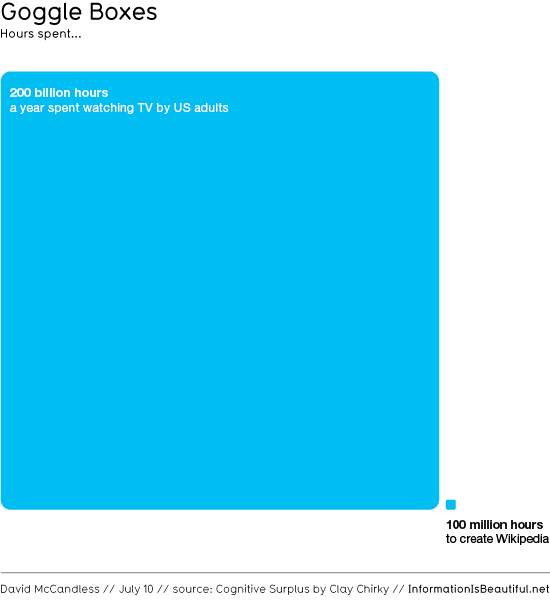

In the 21st Century, when suddenly big user-generated content projects appeared (Wikipedia, Linux, Apache, but also Facebook, Flickr, and Ushahidi), one of the questions raised was about the sustainability of these projects, connected to the idea of “where did the time come from to produce this content?” – At Web 2.0 Expo 2008 and later in his book Cognitive Surplus (2010) Clay Shirky gave where he argues that we are finally able to activate the cognitive surplus generated by industrialization which up to now we had squandered away by watching television.

Television was a solitary activity that crowded out other forms of social connection. But the very nature of these new technologies fosters social connection—creating, contributing, sharing. When someone buys a TV, the number of consumers goes up by one, but the number of producers stays the same. When someone buys a computer or mobile phone, the number of consumers and producers both increase by one. This lets ordinary citizens, who’ve previously been locked out, pool their free time for activities they like and care about. So instead of that free time seeping away in front of the television set, the cognitive surplus is going to be poured into everything from goofy enterprises like lolcats, where people stick captions on cat photos, to serious political activities like Ushahidi.com, where people report human rights abuses.

This transformation from a mass society with its one-to-many media (television) to a network society of many-to-many media (web 2.0) allows us to capitalize on idle time. By segmenting value chains into modular and granular tasks, where anybody can chime in anytime and anywhere.

Shirky’s idea of idle time, however, only touches the surface of the concept. Idle time spent in front of the television that can be reallocated into socially meaningful values makes up a big chunk of the cognitive surplus that we will be able to capture in the next years. However, the bigger part will be captured, when we are able to transform actual idle time into productive time: the idle time when waiting for something/someone, the idle time of the disenfranchised on this planet, the idle time of being between tasks, and the idle time of not working on what fullfills us. So, idle time is about empowering those that are not yet empowered, but also about when you are in the board meeting and bored. Idle time is everywhere! Think of it through the lense of fractal geometry – idle time is self-similar. Once you start looking, you will find it in all aspects of life. My back of the envelope hunch would be that we can multiply Shirky’s number by at least two or three.

Idle Time vs. Down Time: Managing our Wetware Needs

But as soon as we have solved this puzzle, where all this productive capacity for our common futures will come from, we come to the next Luddite summer worry (actually, one of the most emailed articles in the NYTimes this summer):

The technology makes the tiniest windows of time entertaining, and potentially productive. But scientists point to an unanticipated side effect: when people keep their brains busy with digital input, they are forfeiting downtime that could allow them to better learn and remember information, or come up with new ideas.

“Almost certainly, downtime lets the brain go over experiences it’s had, solidify them and turn them into permanent long-term memories,” said Loren Frank, assistant professor in the department of physiology at the university, where he specializes in learning and memory. He said he believed that when the brain was constantly stimulated, “you prevent this learning process.”

The findings are to be taken seriously and it clearly means that we need to be careful with how we deal with our idle time. In the digitally networked age, we need to take responsibility for our sanity. We need to learn how to schedule downtime and offline-time. But theoretically, that should be easier, because now we can manage our interfaces to the digital network, by blocking incoming information.

And this brings me back to the Amazon Kindle: The Kindle does only one thing, it lets you read books. It does that particular well, with a look that is distinctly Steampunk and after 48 hours it clearly seems to be one of those devices that actually allows you to manage your brain cycles and give your brain that downtime that it needs to solidify impressions into knowledge.

Sketching a Planetary Public Policy Approach

As I am wrapping up my time at the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy, it is time to write down some of the lessons I learned here at Erfurt University, where Martin Luther developed some of the frameworks for Information Revolution I. The Willy Brandt School is a brave experiment in bringing together students and young professionals from over 40 countries to rethink public policy. It is an experiment that is important in our days, where we are confronted with huge challenges on this planet. One day last year, while walking to my lecture, it hit me that we are working on the project of planetary public policy. I then wrote a short blog-entry that I always wanted to expand:

Planetary thinking is a term introduced by Martin Heidegger, to reflect the role of philosophy (a Greek/Western concept) in comparison to other systems of thought. Planetary public policy balances different approaches to public policy problems, reminds us that problems come in all sizes (local to global), that we can learn from each other, but that solutions need to be “tropicalized” (adapted to the local context). If public policy is about thinking about having a structural impact, then planetary public policy is about “rocking the planet.”

Planetary public policy combines (a) an acceptance of global problems (climate change, trafficking of women, drugs, weapons, etc.), with (b) an appreciation for comparative learning in public policy (e.g. issues of birth control, slum dwelling, public transportation, crisis management are similar in kind in very different environments), and (c) a sensibility for inter-civilizational exchange of ideas concerning our planetary publics. It is a simple doctrine, but remember territorial sovereignty, the doctrine that has been guiding our thinking and doing for the last 300 years is just as simple. Simple grammars allow for surprisingly complex frameworks. But in the 21st Century, no public policy school can ignore it.

Looking back…

The doctrine of territorial sovereignty developed as part of the transformation of the medieval system in Europe into the modern state system, a process that is linked to the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. The emergence of the concept of sovereignty was developed in analogy to the Roman civil law concept of private property. Both emphasizing exclusive rights concentrated in a single holder, in contrast to the medieval system of diffuse and many-layered political and economic rights. Within the state, sovereignty signified the rise of the monarch to absolute prominence over rival feudal claimants such as the aristocracy, the papacy, and the Holy Roman Empire. Internationally, sovereignty served as the basis for the anarchic nature of the international system and for its ground rules like the exchanges of recognition on the basis of legal equality, diplomacy, and international law. This led to an international system where states were responsible for their own security and self-sufficient in their social and economic needs.

However, with globalization we moved into a world where somehow these two core rules of the international system are broken. we are moving into a world where states are not reliant on themselves in terms of economic production anymore, and neither are they in terms of security. The most basic question we would ask you is, who of you is wearing clothing that’s made in just one country, at this moment. Even Lederhosen, the typical Bavarian dress, all of them, including the Burghausen style are produced in India.

What we are missing is a unifying doctrine that allows us to place our actions in such a world. Territorial sovereignty has lost its grip over us, but planetary thinking is only slowly emerging. Here are the three basic tenets of this emerging doctrine:

Accepting Global Problems

Global problems become global by being referred to as global. Even if the impact of climate change will be different locally, we have firmly constructed it as a global problem. But others less so. Last year, our planet’s population lost $9.3 billion to 419 scams. 419 is a paragraph number in the Nigerian penal code, in the law, which deals with a very specific cyber crime, which is basically have you ever received an email that said,

I am a princess from Nigeria, and my dad left me $80 million in a bank account that I need to transfer out of… Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Mexico, Argentina, Texas, or Southern Bavaria. I need your help to do that, and I will be of course very helpful in giving you 50 percent of what is in the bank account if you help me.

Is that a global problem? Should it be constructed as such?

Comparable Local Problems

Planetary public policy assumes that there are local problems that we can compare to each other and learn from each other. For example, squatting on public lands. What is the Malaysian solution to squatting on public lands versus what is the Mexican solution to squatting on public lands versus what is any other country that has that problem? For a long time, we had assumed that local contexts would be so different that learning across continents would not take place.

Inter-civilizational Meaningful Conversations

Inter-civilizational Meaningful Conversations remind us of the question, how can we develop a fair platform on which we can have a conversation? A conversation between different cultures and through space and time. And that, of course, is the challenge we are facing in the Brandt School, with students from more than 40 countries. But it’s also the challenge that we have to face when we are trying to solve this issue of humanity surviving on this planet.

So public policy in the 21st Century needs to focus on global problems, comparative public policy challenges, and inter cultural, inter civilizational meaningful conversations.

Ignoring the ROI of Openness

I am back from Berlin, where we were discussing at the google collaboratory how to evaluate the impact of open government. While the excitement about enterprise 2.0, government 2.0, and open government has been building, critical voices in organizations have questioned the return on investment (ROI) of such projects. 2.0 projects are often still looked upon as insignificant or superfluous. The now classical response to this has been to allude to the ROI of successful projects:

This approach of utilizing the ROI framework to defend 2.0-strategies, however, has several flaws, (a) it might have been a lucky shot, (b) it might not be sustainable, (c) contests might not focus on what citizens need (d) any impact below a certain threshold, let’s say $ 1 billion does not carry weight in big governmental or corporate organizations, but (e) most importantly, ROI is the wrong tool to evaluate success of enterprise/government 2.0 projects, because most of the value is accrued with the consumer not the producer of the value.

If we look at the most successful 2.0 projects of the last years, we see a pattern, where the ROI is not a relevant indicator to evaluate the project. One of the first big 2.0 projects, Wikipedia, destroyed the encyclopedia industry, but is not generating major revenues. Couchsurfing and sites like http://airbnb.com/ or http://www.crashpadder.com/ are taking big bites out of the Hotel industry without generating equivalent returns. Open Street Map is having a huge impact on the mapping industry, one of the most profitable industries of the last years. Dynamic ridesharing is creating a secondary mobility infrastructure in most countries, basically competing with our complex integrated public transport systems such as the German Railway, with revenues of more than 10 billion euro in passenger transport per year or shorthaul flights. The combined revenues of the 5 major German ride sharing companies is way less than $ 10 million, but the impact on the lifeworld of their users is dramatic.

There are three lessons to be gleamed from this:

- the impact of 2.0 project are not to be evaluated in ROI, but in consumer-focused metrics (shadow prices, counterfactuals, reduction in average cost, rate of demonetarization, etc.). Ideally, not in monetary terms, because 2.0-strategies aim to de-monetarize.

- for corporations, 2.0 strategies go way beyond “normal” cannibalization strategies. They focus on the de-monetarization of industries. Therefore, as strategists, we need to ask, how can we generate a revenue flow that does not inhibit adoption, but sustains the effort.There is no choice, either we do it, or someone else will do it.

- For public value strategists that are not entrenched in existing practices this is a dream-come-true. You can now recreate a multi-billion-dollar infrastructure (the German railway system) with a web-page.

If this does not sound like a fun scenario from the perspective of an existing organization (be that governmental or private), be assured that there is nothing you can do against it. The two mega-trends driving the development are the dematerialization of the economy which has been going on for over one hundred years (the weight of the US economy per dollar of GDP has been decreasing more than 100-fold in the last century) and the implosion of transaction costs of organization through digitization and the rise of n-to-n (peer-to-peer) media are leading to new forms of organization (open value chains) and new products and services that can be digitally provided at basically zero marginal costs.

An analogy of what is happening today can be seen, when we look at the historical institution of medieval knighthood, probably the most expensive and sophisticated approach to individualized fighting and organization of social and cultural life in the history of humanity. In 1386, at the battle of Sempach, a “web-startup” consisting of Swiss peasants defeated the Austrian knights, by pushing them down from their high horses by using long poles. Not very sophisticated, but sufficient to get the job done. Expect more of that today.

When in Berlin, I also had breakfast with Peter Scheufen, the CEO of Skobbler, a smartphone navigation company that was globally the first to utilize Open Street Map in its core navigation product and that is making the navigation industry very nervous. Peter sees his role as a negotiator between the world of the voluntary mappers, software developers that might want to build applications on top of his server offering, and consumers that expect a working navigation product for as close to free as possible, and believes he can build a business model where he can generate a non-intrusive revenue stream for his company. Navigating these waters is not easy, but it can be very rewarding for all of us, who believe we can have a positive impact on this planet and generate revenues, by figuring out how to generate revenue streams that do not disturb the value chain. So, ignore the ROI-issue and focus on the big picture of (public) value creation!

Author of machiavelli.net, proud father of three, interested in shaping network society. Welcome to my blog.

Author of machiavelli.net, proud father of three, interested in shaping network society. Welcome to my blog.